Comment 1

From Milling About to Deadlock: When hierarchies go topless

The idea of the social contract is often mentioned and seldom

understood. Politicians use that term but nobody seems to know what

they really mean by it. 17th century thinkers spoke as though there were

actual conversations or consultations in which these matters were

determined. In reality these matters must have taken place over a long

time and in various contexts. I will try to investigate what

may have happened by imagining a simple case of contract negotiation.

Imagine that a ship sank and a

group of orphans became lost on an island someplace. They all spoke the

same language but there was no older person to lead them. They gathered

fruit and bird eggs to eat. Some kids wanted to rob and eat the bird

eggs and fruit the other kids had gathered. The kids who had their food

taken from them would naturally be angry about that. After a while

the kids who regularly lost food might band together to protect each

other. It might happen that separate groups came into being and

sometimes they might not agree. Gang fights might occur. Some child

with vision, some child who could comprehend the whole situation, might

then emerge to become a leader of all of them. I think it usually

happens in an informal group that a person will emerge as the one whom

almost everybody agrees has the best sense. He or she doesn't have to

be the strongest or even the most intelligent, just the one whom most

people think is pretty fair. That person's leadership would depend

heavily on trust.

A small group like this could

evolve in several different ways. Perhaps the leader would be a very

strong person who could force people to do what he or she wanted. That

would not work very well in the long run because some of the people

would take advantage of being friends with the leader and other people

would lose out. The people that lost out wouldn't be very loyal to the

group. Then the leader would only be the leader of his or her clique

and there would be a second group that would become opposed to the

leader. The second group would find its own leader and then there would

be a chance for a sort of primitive war. The two groups might separate,

but then each group would be weaker than the original group that

contained all of the people.

In trusting someone else with authority, one must believe that

one's one interests and those of one's group will be respected. A

constitution will give a legal basis for this trust by protecting the

interests of minorities and preventing a dictatorship of the majority.

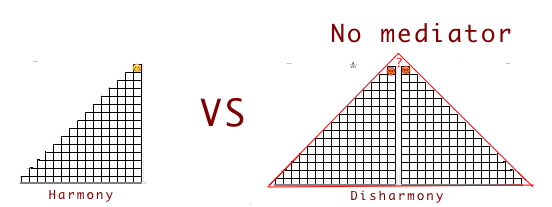

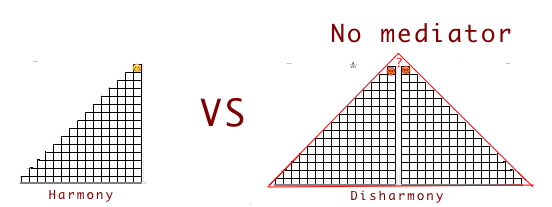

So here is a very important

principle to mark out: For peace and cooperation there needs to be

someone who is not the leader of just one part of the society. If there

are two or more factions in a group and each faction has a leader, then

that is effectively a split society. Whenever there is conflict there

will be no authority to solve the conflict. There will be nobody in the

middle to mediate any conflict. We can often see this kind of fight

brewing up in a modern society. It may be that a large factory has a

workforce that is organized into a union. The factory owner says, "I'll

give you workers 1/2 an ounce of silver for every hour that you work."

The workers say, "That's not enough. We want 3/4 of an ounce." Then the

workers go on strike, and the factory boss hires thugs to come in and

break up the strike. To avoid this kind of fight there needs to be a

third party who is neither a factory boss nor a worker, and that person

(or that part of the government) needs to have authority to come in and

tell everybody what to do.

Suppose that the third party, the

arbitrator in this situation, says workers should get 5/8 of an ounce

of silver per hour. The factory owner is unhappy and he says, "I'll get

you fired!" The workers are unhappy and the union says. "We'll

work against your superior in the next election, and you'll get fired!"

But if the arbitrator has been open and clear he may be okay in this

situation. He will say, "I looked at the accounts of the factory, and

if they gave you workers 3/4 of an ounce, then they couldn't afford to

buy enough raw materials to keep all of you at work. On the other hand,

if the factory only gives you 1/2 an ounce of silver that will let the

boss walk off with a tremendous amount of money that he doesn't really

deserve." When the election starts there are plenty of other people who

don't stand on the side of the factory owner and don't stand on the

side of the workers, and they can see that the arbitrators have been

fair. So in a society that keeps everything open and aboveboard, voters

will generally be able to figure things out correctly and keep the

arbitrator in his job.

I'm working with a really simple

society here. I'm making a very simple model society. However, the

principle exhibited here is an important one: Control should pass down

from the head of state to something like a labor ministry and then to

somebody who does the arbitrating. One kind of feedback goes back up

the chain of command. The arbitrator tells the labor ministry, "I

succeeded in doing the job you gave me. Mission accomplished." The

labor ministry tells the head of state, "Everything is working all

right with labor affairs these days." And the head of state feels that

he doesn't have anything to worry about with regard to labor affairs.

It is important to note that the head of state does not need to do much

more than to set the general goal of keeping labor relations in good

shape. It can be up to subordinates to determine exactly how to achieve

those goals.

It isn't only that signals go down

and back up the chain of command, however; feedback from the general

public also goes to each level of that chain of command from people in

the community. They may say that the laborers aren't being treated

fairly, They may complain that the labor ministry is not doing its job

well enough, or they may complain that the head of state is not working

the way he should. This kind of feedback makes the arbitrator look more

closely at what has been done, it may prompt the labor ministry to

check on what the arbitrators have done, and it may warn the leader of

the country that something is going wrong and he had better fix it

before election time.

Once many people are involved

things can get complicated. The emperors of China discovered that what

they ordered didn't always get done, and they might not find out. In a

bureaucracy that had several levels, each time the emperor's order went

down a rung it could change because each level of administration had to

figure out how to implement the emperor's directives. Because officials

had their own subjective take on things, the implementation process

could slant things away from what the emperor would have wanted. Then

when the orders went out among the people and produced results in the

real world, news of what was accomplished needed to go back up the

chain of command. At each level information from lower levels would be

aggregated and the results might be sweetened to make the official look

better. So by the time a report reached the emperor it might not be

accurate enough to be truly useful.

When the emperors of China finally

twigged to this kind of thing going on, they invented a new kind of

official called a censor. The job of a censor was to go out into the

countryside to find what was really going on. If he found that anything

was going wrong he could get the concerned officials in a lot of

trouble.

In a free society this kind of

investigation is often performed by the press. Investigative reporting

can reveal to the administration what its subordinate officials are

doing, and it also reveals hidden misbehavior to the voters. So freedom

of the press is a strong guard against tyrannical government.

Mao Zedong said, "Power comes from

the barrel of a gun." Ultimately, that is the justification for the

rule of the Communist

Party over China. If asked, "What right do you have to rule over the

people of China?" the only answer is, "We rule because we have the guns

and other tools of compulsion." While such a government

may be nervously aware of the power of the masses, it will have

virtually no reason at all to be protective of the rights of minorities.

At the other extreme of government

would be a formless direct democracy, a society in which every decision

would be reached by majority vote. How would you feel if disposal of

your house, your spouse, your

children, your possessions, etc. were all subject to the whims of

public opinion? They could all be taken away from you because the

majority of people in your community wanted to do something with them.

What happens if many people in a

country like China decide that they did not give the government the

authority to rule over them and so they work to take that authority

away? There are no effective feedback mechanisms, so there is no

established way to curb government excesses by vote, petition, etc.

Their authority coming out of the barrel of a gun, the only way to

change the situation is to use some kind of force to oppose them.

Gandhi used force to oppose the British Raj, but it was not the violent

kind of force dependent on weapons. There may be a hundred modalities

to produce change in a state like China, but they will go beyond the

kind of feedback that can be ignored.

When two or more power groups have

no superior to mediate among them and decide what route to take,

societies may deadlock or fission. The United States is currently in

this situation. There are several power centers that crowd around the

missing apex position: the Supreme Court, the President, two major

political parties of nearly equal strength, and the Armed Forces.

Theoretically, the Armed Forces are subordinate to the President, but

the same strategic separation that acts against their becoming the

instrument of a president in domestic affairs also makes them immune

from patronage debts to the president. The last general to challenge

the authority of the Commander in Chief was Douglas MacArthur. He

received no effective support in his efforts to control foreign policy.

However, it is still conceivable that in some time of intense

dysfunction of government the Armed Forces might perform a coup. Even

the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff has no "power of the gun" to

ensure his dominance. So it is possible that an army or a battalion

might perform a coup. Alternately, a president might use his power as

Commander in Chief to assume autocratic power. The probability of any

of these developments is very low under any range of conditions thus

far experienced.

The current standoff between the

two major political parties, however, is a serious dysfunction. There

is no constitutional preparation for handling this kind of lock-up of

the mechanisms of government.* There is no officer of government who

stands above them and is empowered to force a compromise. The Founders

of the Republic evidently expected that no faction would endanger the

nation in pursuit of its own interests. They were wrong.

When a country is split among

several unconnected hierarchies of control that have no superior

controller, it is not clear how to depict the organization of the

country. It is not even quite clear what makes this complex combination

of humans capable of functioning as a nation. It is conceivable that

all the members of one ethnicity, religion, or other group held

together by some non-essential trait would form a component of the

nation, have its own system of social controllers, etc. Another

component of the same country might be located in a single region. If

each of these components behaved in most ways like a state, then an

intractable problem would arise whenever two or more of these

components came into conflict. The same general situation prevails in

the world as a whole, many nations jostling with each other and lacking

any superior organizational unit to mediate among them. It is clear why

there is still no world government: The nations of the world are

unwilling to give up sovereignty.

Trust is hard won and easily lost.

In a primitive tribal society the position of chief may not be

hereditary. It must in any case depend on trust. An individual with

aspirations will never become a so-called "medicine man" or shaman

unless he or she wins the trust of the community. Similarly, in the

world community it would be necessary for some group of individuals to

somehow set aside their individual national identities and begin to

function as independent executives or mediators over all nations. Similarly,

in situations wherein there are two or more strongly opposed power

groups it will be difficult for a member of any one of them to become

the leader of all.

__________

* In the Senate of the

United States, a tie vote can be broken by the president of the senate.

However, in the House of Representatives an impasse cannot be broken by the Speaker

of the House.

Last revised 9 January 2016

guests